A vital piece of gas engines, combustors—the chambers in which the combustion powering the engine occurs—have the problem of breaking down due to fatal high-frequency oscillations during the combustion process. Now, through advanced time-series analyses based on complex systems, researchers from Tokyo University of Science and Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency have found what causes them, opening up novel paths to solving the problem.

In a breakthrough, published in Physics of Fluids, a team including Prof. Hiroshi Gotoda, Ms. Satomi Shima, and Mr. Kosuke Nakamura from Tokyo University of Science (TUS), in collaboration with Dr. Shingo Matsuyama and Dr. Yuya Ohmichi from the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA), have used advanced time-series analyses based on complex systems to find out.

Explaining their work, Prof. Gotoda says, “Our main purpose was to reveal the physical mechanism behind the formation and sustenance of high-frequency combustion oscillations in a cylindrical combustor using sophisticated analytical methods inspired by symbolic dynamics and complex networks.” These findings have also been covered by the American Society of Physics in their news section, and by the Institute of Physics on their news platform Physics World.

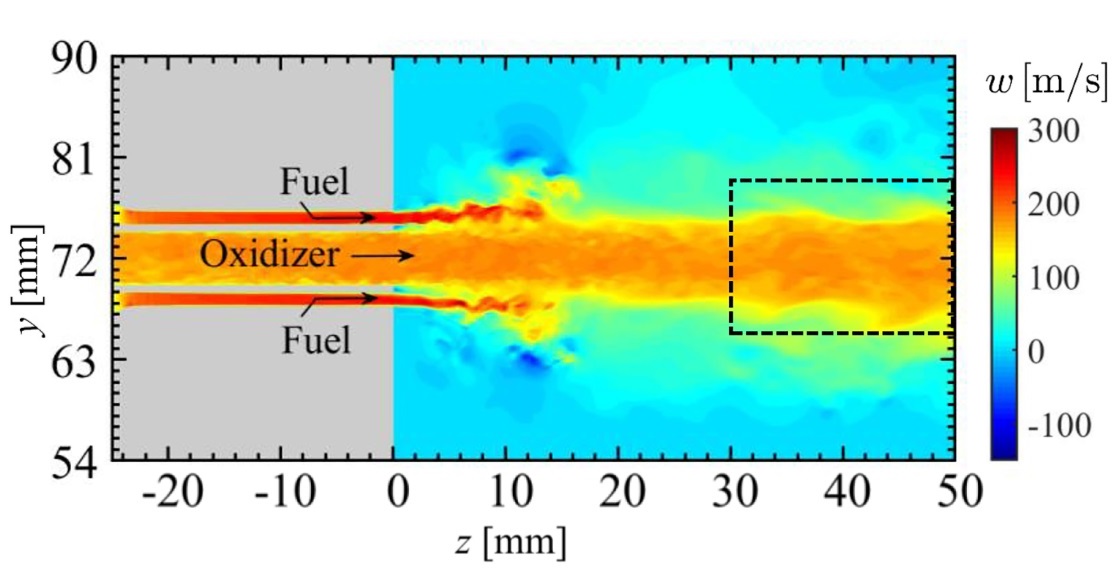

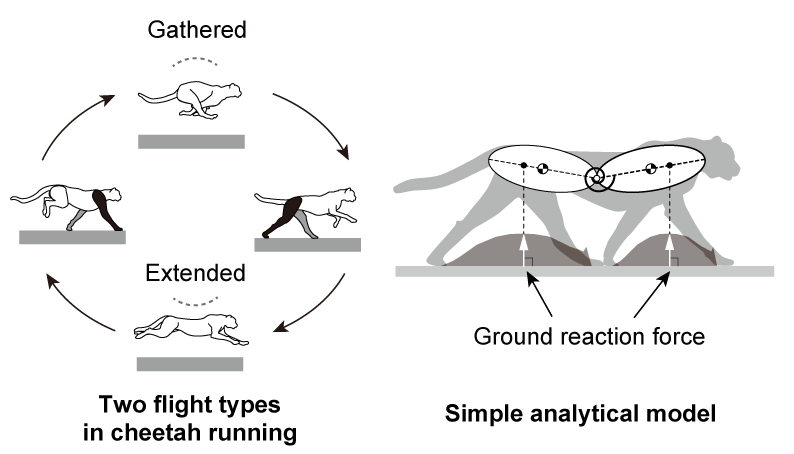

The combustor the scientists picked to simulate is one of model rocket engines. They were able to pinpoint the moment of transition from the stable combustion state to combustion oscillations and visualize it. They found that significant periodic flow velocity fluctuations in fuel injector affect the ignition process, resulting in changes to the heat release rate. The heat release rate fluctuations synchronize with the pressure fluctuations inside the combustor, and the whole cycle continues in a series of feedback loops that sustain combustion oscillations.

Additionally, by considering a spatial network of pressure and heat release rate fluctuations, the researchers found that clusters of acoustic power sources periodically form and collapse in the shear layer of the combustor near the injection pipe’s rim, further helping drive the combustion oscillations.

These findings provide reasonable answers for why combustion oscillations occur, albeit specific to liquid rocket engines. Prof. Gotoda explains, “Combustion oscillations can cause fatal damage to combustors in rocket engines, aero engines, and gas turbines for power generation. Therefore, understanding the formation mechanism of combustion oscillations is an important research subject. Our results will greatly contribute to our understanding of the mechanism of combustion oscillations generated in liquid rocket engines.”

Indeed, these findings are significant and can be expected to open doors to novel routes of

exploration to prevent combustion oscillations in critical engines.